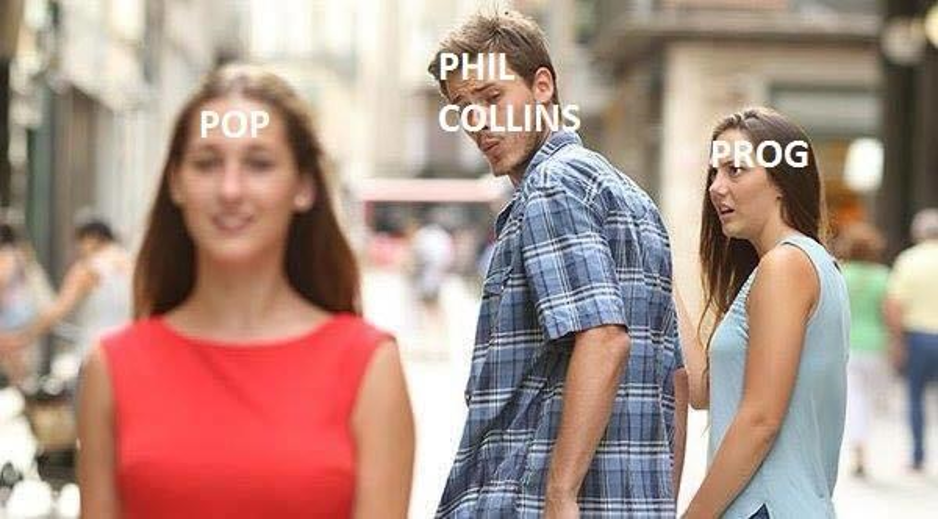

In November 2015 stock photographer Antonio Guillem posted a picture on Shutterstock. It showed a young man walking in a city street with his girlfriend. His head is turned back and he ogles a woman walking in the other direction. His girlfriend has a look of disgust.

The picture was shot in Gerona, Spain, and it was one of a number of pictures that Guillem had made featuring the same three people, his regular models. The image was even part of a series exploring fidelity.

In January 2017, the image turned up on a Turkish Facebook page. Now the distracted boyfriend was labelled as the musician Phil Collins, and he was distracted by “pop” from his girlfriend “prog.”

According to Meme Documentation, a Tumblr that tracked the history of popular memes, the maker of that image had been inspired by a political meme he had seen earlier that day. That meme showed the distracted boyfriend as Communism distracted away from a potato by a luxury meal.

A month later, the image reappeared, this time with a label urging people to “Tag that friend who falls in love every month.” Within seven months, the post had picked up more than 28,500 likes. That summer, another version of the meme appeared on Reddit, and showed the distracted boyfriend looking back at a “solar eclipse” and away from “scientific evidence supporting the dangers of staring at the sun.” It gained more than 31,000 points and 130 comments within just 24 hours. Soon the meme was everywhere, with the labels changed to reflect media companies’ distraction from text-based content to video content; young people’s preference for socialism over capitalism; and Zeus being distracted away from Hera by literally everything and anything.

The Meme Documentation tumblr defined a meme as a “packet of information that is spread within a culture.” It also laid out four characteristics that memes share: they’re popular without being so mainstream that they’re no longer cool; they can inspire derivatives that change the original post, a significant different to viral images; they’re spontaneous; and they’re funny, at least to enough people to enable them to be created, changed, and shared.

That combination of popularity, participation, and entertainment is powerful. It provides a channel for information to spread through a society, communicating not just a picture or a joke, but an idea, a general feeling, or a brand’s identity.

Professional Meme Making

The Distracted Boyfriend meme was created for fun. It worked as a way for people to share their ideas and their frustrations, not to make money. Even Antonio Guillem saw few benefits from the popularity of his picture. In an interview with Wired, he noted that his top-selling images generate between 5,000 and 6,000 licenses a year. The meme photo averaged about 700 sales a year.

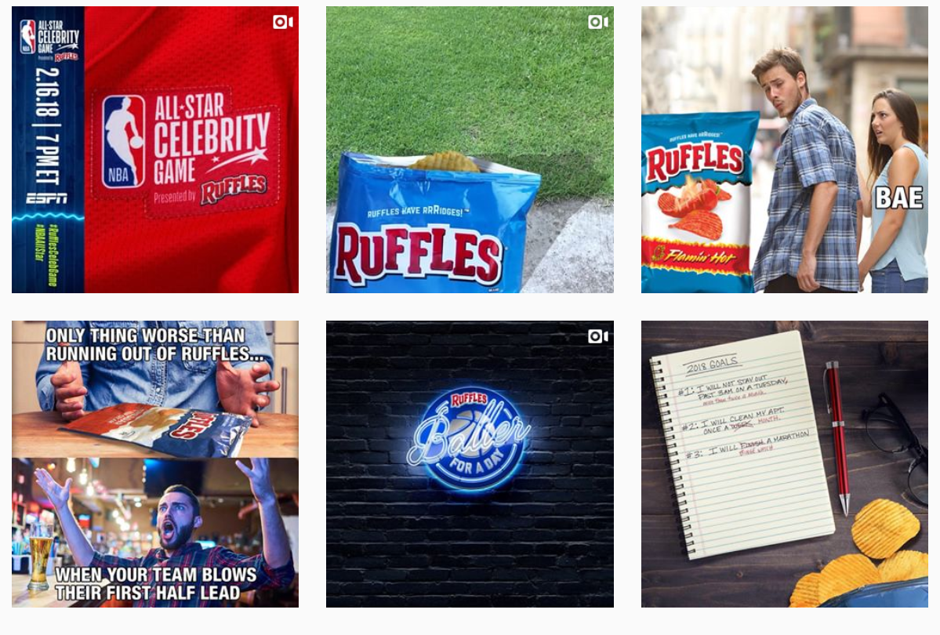

But not all memes are made for fun. Brands have seen the value of creating images and messages that have built-in virality, and they’ve tried to cash in on that potential reach by paying professional designers to create memes for them.

Browse through the Instagram stream of Ruffles potato chips, for example, and you’ll see not just promotions and pictures of celebrities eating chips. You’ll also see attempts to both cash in on memes and spark new ones. You can even find the Distracted Boyfriend meme.

That mixture of new memes and repurposed old memes is typical of how professional meme-makers attempt to produce memes for brands. It’s difficult to estimate how many people do this kind of work professionally. Much of it is produced either in-house as part of the output of corporate social media teams or by design shops and freelancers. A search for “meme” on Fiverr returns more than 500 freelancers offering to create “dank memes,” “viral and engaging social media meme videos,” and “photoshop memes for cheap.” Prices range from Fiverr’s archetypal five bucks to around $30.

More lucrative work though is available. In 2017, as Distracted Boyfriend was distracting people across social media, a rapper called Ka5sh was making a living creating memes for record labels. In an interview with NBC, he explained that his entry into the world of professional meme-making started with an appeal on Twitter for someone to “hook me up with a job at a social media thingy”. His first job came from Mad Decent, a record label, which paid him $100 to create a post to support a record release then share it on his own Instagram account. Word spread and more labels asked him to produce memes. He spent much of that year earning a living from meme-making, and by disseminating those memes across a range of specially-prepared accounts.

For Conor Diskin, the entry into professional meme-making came even earlier. He graduated from Maynooth University in Media Studies in September 2015, and started looking for work. On a media graduates Facebook group, he saw a jobs ad for a “content creator,” and soon found himself creating content for CollegeTimes and TeenTimes.

Writing on his blog, Diskin explained that the sites had a four-step business plan: they identified an audience on the Web and on social media; they engaged with that audience through content; they converted that audience into a loyal following; and then they ran sponsored ad campaigns to monetize that audience.

For these kinds of publishers, Diskin argues, reach is everything. Content has to take advantage of the algorithms used by social media platforms to rank content in order to appear before as many users as possible. Liking posts isn’t enough; users have to either share or comment under the post. Ideally, a post will eventually end up in front of an influencer who will send it out to thousands of people, some of whom will copy it and promote it further.

Diskin would have to make as many as twelve memes every day, trying to convert trending topics, pop culture imagery, and current affairs into new ideas that could become popular memes. With that pressure, and churning them out at a rate of more than one an hour, it’s no surprise that like the variation integrated into memes themselves, not everything that Diskin produced was original. He’d look through Reddit, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram for memes that looked like they were taking off, then redesign them and add the company’s logo.

“Some would call this process stealing,” he writes on the blog. “I called it inspiration so I could sleep at night.”

Diskin now works for a sports nutrition company, managing their social campaigns, blog content, and digital marketing campaigns. He says he’s not in the meme game any more (“sadly”) but the experience did bring him transferable skills.

“All marketing is generally trying to relate your brand to trends and piggyback on what’s currently being talked about online,” he says.

But the process of creating memes, and the business model behind them, haven’t changed, he argues. Brand pages like Boohoo, which intersperses viral videos between product pictures, post completely random but relatable memes in order to win organic engagements from people it can then target with ads. Few of those videos are original, says Diskin.

“In my experience if I was to give a proportion of what is completely original from people working as content creators like I was, I’d say between 20 and 30 percent max.”

That lack of originality among meme-makers has caused problems. No one expects individuals to credit the creator of a meme or ask their permission before sharing it on their own streams. Antonio Guillem told Wired that he wasn’t worried about the use of his images in memes. Although they haven’t given him any kind of profit, weren’t sold by the microstock agencies and are being used without the proper licenses, the people who share them are acting “in good faith”. He did, however, add that he would pursue legal action when the images reflected poorly on him or on his models.

Ka5sh has talked about an “unspoken rule in the meme world” to give credit whenever possible. A meme-maker who finds a meme with a watermark should tag the original creator. They should also respect any requests for tags from people who can show the content is theirs.

If credit is an unspoken rule, it’s one that’s probably more broken than respected. Diskin notes that while credit is sometimes given in the comments, something that has become “more common” in recent years, “it’s still not standard.” In February 2019, Elliot Tebele, founder of FuckJerry, an Instagram account with around 15 million followers and a reputation damaged by association with the Fyre Festival, apologized for copying memes and jokes without permission.

“In the early days of FuckJerry, there were not well-established norms for reposting and crediting other users’ content, especially in meme culture,” he wrote. “Instagram was still a new medium at the time, and I simply didn’t give any thought to the idea that reposting content could be damaging in any way.”

The company’s new policy, he added, would be to not post content “when we cannot identify the creator, and will require the original creator’s advanced consent before publishing their content to our followers. It is clear that attribution is no longer sufficient, so permission will become the new policy.”

That makes for an uncomfortable position for professional meme-makers. Creating original content takes time, which is hard to come by when you have less than an hour to dedicate to each one. But tracking down original creators and landing permission takes even longer. Meme makers know that original creators, whether they’re photographers like Antonio Guillem or new meme designers like Ka5sh or Conor Diskin, will turn a blind to sharing and reposting when the brand spreading the meme is small. But once the platform becomes big and starts making real money out of that copied content, they can expect the original creators to start demanding attribution, permission, and perhaps even paid licensing.

How to Create a Successful Meme

One solution would be to switch from the mass production of memes—some copied and some created—to a careful focus on original, individual memes. They’d take more time to produce but they’d have a higher chance of success. That would represent a large change in the way that commercial memes are produced, and it’s not done now because it’s never easy to predict which memes will be popular. Diskin says that when he was making a dozen memes a day, only two or three of those memes would do well. “Of the couple of hundred I made I’d say about 20 went viral enough to gain a reach of over a million people.”

Meme makers are also aiming at a moving target. Social media habits change. Users are no longer sharing on Facebook, Diskin warns, but Twitter is making a comeback for viral tweets, and people do share frequently on Instagram stories. “This is where you can get the most coverage but [it’s] harder to track.” Messenger apps have now become important vectors for meme-sharing too.

The goal is to make a meme that people won’t just like but will share and include a friend in the comments. Users have to do more than laugh; they also have to act. That often means riffing on a theme that’s permanently a concern of the target audience. For Diskin and his student market, that meant memes about hangovers and waiting for payday tended to do well but there were always surprises.

“It’s a test and learn thing where you generally see what works well with your following and how they interact with them,” he says. “Then even when you think you’ve cracked it you can end up having one that you weren’t sure of going viral.”

Distracted Boyfriend sat for two years on Shutterstock before an obscure Turkish politics group picked it up and used it to make a comment about communism. Before the year was out, it had been taken up and spread around the world, inspiring thousands of new versions. For professional meme-makers that should represent frustration at an amateur’s giant success. It’s more likely to be raw material that they can use to create their own memes.

Recent Comments