Hahna Alexander found an opportunity. She discovered it while she was at college and wanted to make walking on campus at night safer. By embedding a set of gears in the sole of a shoe, she was able to turn a downward step into rotational movement. That movement powered a small generator in the heel and made the shoes light up.

It didn’t take long before Alexander realized that the potential of her invention was much greater than lighting up dark streets. At a time when everyone has mobile phones, and no classroom, café, or airport waiting lounge ever has enough electrical outlets, those same shoe-based generators could be used to charge a battery that could then be used to charge a mobile device. Simply walking would be enough to give people all the power they needed to keep their phones working all day.

Together with classmate Matthew Stanteon, Alexander formed a company and raised $60,000 on Kickstarter. She created prototypes and tested them on treadmills. She refined the shoe and the generator, and eventually produced a product that she believed worked “pretty well.”

It was then time to take the footwear out of the lab and give it to people to test.

It’s a familiar story. Every entrepreneur is bursting with ideas and believes they’ve found a golden opportunity. but the path from spark to success isn’t easy and it certainly isn’t guaranteed. We take it for granted that not all business ideas are good and not all opportunities pan out. But should we? When a business owner hires a new employee, they check the resumé, call references, and assume that the people they hire are going to work out. Before businesses launch new products, they talk to the market, and conduct surveys. Before they roll out a marketing campaign, they test headlines and offers to find out which have the most powerful effect. Too often though, entrepreneurs and founders rush into a new opportunity powered by little more than passion, excitement, and self-belief. Are there better ways to identify genuine opportunities? How can they value them? And are there processes that businesses can use to increase their chances of success?

What Is an Opportunity?

An opportunity is a set of circumstances that, with effort and resources, can generate value. A business owner invited to pitch their product has an opportunity to land a sale. A new graduate who meets an employer and is asked to submit their resumé has an opportunity to start a new career.

But those opportunities don’t come out of the blue. An opportunity might sound fortuitous but it rarely has anything to do with luck or chance. A manufacturer invited to pitch a product first needs a product to pitch and has to make contact with the person who provides the invitation. That took effort. A graduate would still need the right knowledge and resumé to land the career they want, and they would have had to attend the jobs fair to meet employers. That took effort too.

When we talk only of opportunity, we ignore the work that went into producing the circumstances in which that opportunity occurred. Ideas may be discovered but opportunities are created through a combination of insight and industry. Peter Vogel, a professor of Family Business and Entrepreneurship at IMD Business School, notes that it takes time, work, and resources to turn an idea into an opportunity. He also concedes that not every idea will “automatically” make the whole transition.

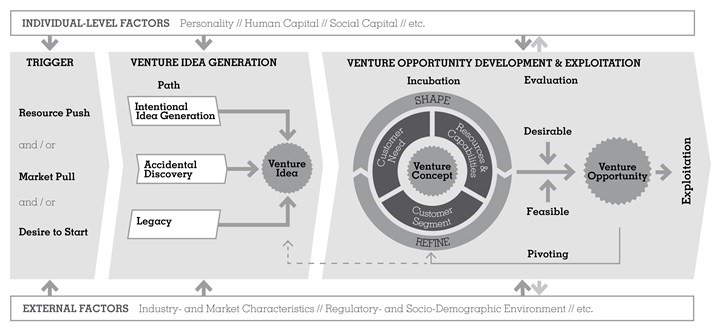

Vogel has laid out a framework that shows where opportunities begin, and describes the process they undergo.

First, a trigger sparks inspiration. That trigger might be something as simple as a desire to begin, but it could also be a “resource push” or a “market pull.” The growth of mobile phones, for example, created a new opportunity for software developers to make small applications. Without the “resource push” of Facebook, there would have been no opportunity for Zynga to make Farmville. Without the “resource push” of mobile phones, Rovio would have had nowhere to put Angry Birds.

Those kinds of opportunities are relatively easy to spot. They build on the success of an opportunity that someone has already built. When a new product takes off, whether it’s in social media or in mobile applications or in drilling technology, other companies will be quick to make the most of that proven opportunity. It was George P. Mitchell’s invention of hydraulic fracturing that made reserves of shale oil into an opportunity that others could exploit.

“Market pulls” are harder. Demand is rarely expressed explicitly. Consumers don’t usually know what they want until they’ve been offered it—and businesses don’t know whether the market wants it until they’ve seen buyers accept or decline it.

One place entrepreneurs search for market pulls is the obstacles and problems that people encounter every day. Hahna Alexander’s idea for electricity-generating boots was derived from the problem that some students faced as they walked across campus in the dark. The rise of mobile phone batteries was a solution to the problem that people faced as they tried to keep their phones charged all day. Wherever there’s a point of friction, there’s always an opportunity for an entrepreneur or a company that can ease that friction and build a business.

In 2018, for example, Bose, a company best known for its speakers and headphones, brought out a new product. Instead of streaming music, Sleepbuds, a pair of wireless earbuds, would only stream a preset menu of ten “soothing sounds,” such as ocean waves and rustling leaves. The idea was to use a version of the company’s products to offer a solution to sleeplessness. Whether the company had really hit on an opportunity would depend on two conditions: that enough insomniacs are willing to pay more than $200 for the chance to hear white noise as they try to fall asleep; and the Sleepbuds’ ability to produce that sleep. If the product doesn’t do what it says on the label, then reviews will be poor and no one will buy it. But if insomniacs find that two-dollar earplugs do the same job just as well, then Bose won’t make any sales.

So it’s not enough for an opportunity to solve a problem. It also has to solve that problem effectively, in the right way, and at the right price. The cost of the solution has to be worth paying.

That cost isn’t always measured in money. Google Glass didn’t fail because it didn’t solve a problem. In 2016, the numbers of pedestrian deaths in the US reached their highest level in more than 20 years, an increase attributed largely to the growing use of smartphones: people are too busy looking at their phones to look where they’re going. That danger hasn’t changed. You don’t need to do more than walk down a road to see the need for a heads-up display that can show directions and messages in real time. A device that allows people to keep up with their messages while also looking out for traffic should have been able to solve an important problem.

But the product’s poor design exacted a cost on using the product that was even higher than its $1,500 price tag. Google Glass might have solved one problem but it gave users a larger one: looking too nerdy for comfort. Measuring the cost and the value of that opportunity is as important—and as difficult—as finding and creating the opportunity in the first place.

How to Measure an Opportunity

It’s the least credible part of any start-up pitchdeck. After explaining how the product works and describing other companies working in the same field, the founders always include a slide showing the size of the opportunity.

And venture capitalists know to take that slide with more than a pinch of salt. Inevitably, the size of the opportunity will consist of a small percentage of the hundreds of millions of people who might possibly use the product. The final number always feels like guesswork so venture capitalists are usually less interested in the figure itself than in the potential for idea to scale from a small number to a large one. The value of the opportunity is less important than the size of its potential.

But the value of the opportunity does matter. There’s never a shortage of ideas so businesses have to choose which ideas to build into an opportunity. That means crunching figures and making predictions.

Stroud International, a consultancy, recommends that businesses use a single representative metric, such as cost per unit, to ensure that all opportunities are comparable. Calculating that metric can be performed using a number of different measures depending on the information available.

Historical information drawn from the creation of a similar opportunity in the past, can be used to predict future returns. That’s useful if a new opportunity is similar to an old one. A drilling firm trying to calculate the values of the opportunities available in two different shale fields can compare the price that the recovered gas would fetch on the market to the sales of previous volumes of gas. But it’s less useful when an opportunity is new or solves a problem in a new way—such as charging phones by walking.

Spot-checking takes the form of small market tests that can be extrapolated across a larger market. KFC’s decision to sell Beyond Meat in one outlet, for example, will allow it to calculate the value of the opportunity of selling fake meats across all its outlets. The problem with this method is that, while accurate, it requires a significant investment. KFC would have had to strike an agreement with Beyond Meats, reconfigure the kitchen in that outlet, re-train its staff, and re-print its menus. The company even turned the outlet green. And while the result will provide a good measure of future revenues, the company’s analysts would still have to bear in mind the effect of geography and novelty as they make their calculations.

The third method that Stroud International recommends is customer surveys, which it describes as the quickest method, but one “more susceptible to mis-valuing an opportunity because of its lesser reliance on facts and data.” Businesses, the organization says, are likely to use surveys when there are no historical or current measures, or when the risk of working on the wrong opportunity is low.

Counting Complexity

The cost of building an opportunity and the value that the opportunity may win aren’t the whole picture. Stroud International also pays attention to the “complexity” of an opportunity, a characteristic which it concedes is much harder to quantify than value or cost.

“There is no empirical formula to calculate an unquestionable complexity number,” Stroud International says in a report.

Instead of trying to come up with an absolute number, companies can instead produce relative figures that allow them to contrast the complexity of one opportunity against another. Factors that affect that complexity include: assumptions about technical difficulty; the number of work hours required; regulatory, legal, or environmental risk; previous failed attempts; and timeframe.

None of those influences is easy to measure but having come up with some sort of complexity figure, a business can then plot the opportunities on a complexity/value graph. They can use the graph to identify the opportunity that appears to promise the greatest rewards for the least effort.

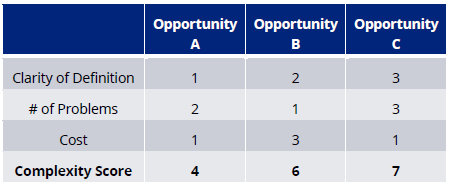

Alternatively, they can also use an opportunity matrix. By awarding scores from 1-5 for factors such as complexity, clarity, or cost, they can compare opportunities to find the ideas that have the best chance of success:

Stroud International’s method of measuring opportunities isn’t the only one. Businesses tend to conduct value opportunity analyses in different ways. A design firm, for example, might try to measure how well a new product model appeals emotionally, aesthetically, and ergonomically among other characteristics. Other businesses might dive into Porter’s Five Forces to analyze an opportunity’s competitive environment and build a score relative to other opportunities currently in place.

From Spark to Product

What all these different methods of identifying and measuring opportunities show is that there is no one scientific way to assess the chances and rewards of success. Entrepreneurs are always brainstorming, surveying, benchmarking, examining the market, and looking for new ideas then trying to figure out which of those ideas have the best chance of making the biggest impact. In general, they take the following steps.

- Identify an Opportunity

They talk to customers and identify points of friction. They look for new demand and keep track of new industry events to see whether a release of new resources has sparked a new opportunity. They make a list of all the possible ideas that could lead to new opportunities.

- Measure the Opportunities

They use historical and current data or customer surveys to start to map numbers onto their ideas. They add figures for complexity and costs, then compare those numbers to find the opportunities that promise the best returns.

- Start Building the Opportunity

Once they’ve identified the opportunity they want to build, it’s time to start working on it. They keep track of the costs to make sure that their early calculations were right, and stay in touch with customers to make sure that the market hasn’t moved since they started building.

Be Ready to Pivot

And it’s important to be dynamic and flexible. When Hahna Alexander passed out the first version of her shoes, the reaction was positive. People loved the idea of being able to charge their phones while they walked… for a while. Soon though, they decided that a pair of flip-flops and a spare battery were more comfortable than wearing a self-charging boot. The product stayed in the closet and the opportunity that Hahna Alexander thought she had discovered—and into which she had poured at least $60,000—turned out not to be an opportunity at all.

So Alexander took the shoe back to the drawing board. She had a product that worked. The cost of using it, like Google Glass, had turned out to be more expensive than the cost imposed by the problem and users had a cheaper solution.

But if Alexander could find a market where the cost of wearing her shoes, rather than more fashionable shoes was negligible, or that placed a higher value on the benefits her shoes delivered then she would still have an opportunity. Alexander made a few alterations to the design. Instead of using the generator to charge mobile devices, she used it to power sensors such as GPS and temperature, and to send out alerts in the event of falls or fatigue. And instead of pitching to students and commuters, she targeted the military, emergency services, and construction crews. SolePower has now partnered with the Army’s R&D department to create a self-sustaining data collection and power source for soldiers.

However you calculate the value of your opportunities, you might well find that the most valuable opportunity isn’t the one you see after you start building it.

Recent Comments