The publication of the Agile Manifesto was meant to solve a specific problem. The speed of software development wasn’t keeping up with changes to customer needs. Decisions would be made at the beginning of the production process that were no longer relevant by the time the software was delivered, sometimes years later. Developers wanted a way of working that could grow with customer requirements, that was more responsive, more timely—more agile. In 2001, a group of leading developers came together at a ski resort in Utah and published a list of principles that they hoped would revolutionize the way their products were made.

Those principles focus on the software industry specifically. The word “software” appears in three of the manifesto’s twelve principles. But a way of working that builds projects with “motivated individuals,” arranged into “self-organizing teams” who aim to “satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery” would always have an appeal beyond the technology industry. Not every business is digital but all customers live in a digital age and many engage with businesses through digital platforms that can benefit from those agile principles. As IT firms have come to define the current business environment—and dominate lists of the world’s wealthiest companies—other industries have started to play close attention to how they work and try to replicate those processes.

The result has been a certain amount of success but also a number of failures. Agile ways of working can be beneficial but outside the software industry, companies can expect plenty of resistance, some large challenges, and no guarantee of success.

ING Gets Into Agile

One company that appears to have made the transformation successfully is ING. The Dutch banking group worked with McKinsey in 2015 to adopt agile ways of working. In an interview with the consultancy, Bart Schlatmann, formerly the COO of ING Netherlands explained why the company chose to act less like a traditional financial firm and more like a hi-tech business like Google or Spotify:

Customer behavior…. was rapidly changing in response to new digital distribution channels, and customer expectations were being shaped by digital leaders in other industries, not just banking. We needed to stop thinking traditionally about product marketing and start understanding customer journeys in this new omnichannel environment.

ING had noticed that customers would start a journey in one channel, perhaps by visiting a branch to talk to an investment advisor, then continue their interaction with the company in another channel, implementing the advice that they had received in person on ING’s website. The bank wanted to make those movements smooth, and saw an agile way of working as the best method of delivering that strategy.

That change included completely reinventing the company’s structure.

In January 2015, all the employees at ING headquarters were told that they were on “mobility.” In effect, they were made jobless. To continue working, they had to reapply for a position in the new organization. The company selected 2,500 people, prioritizing culture and mindset over knowledge or experience. Forty percent of the people who were retained found themselves in a new position. The company also lost “a lot of people who had good knowledge but lacked the right mind-set,” Schlatmann said.

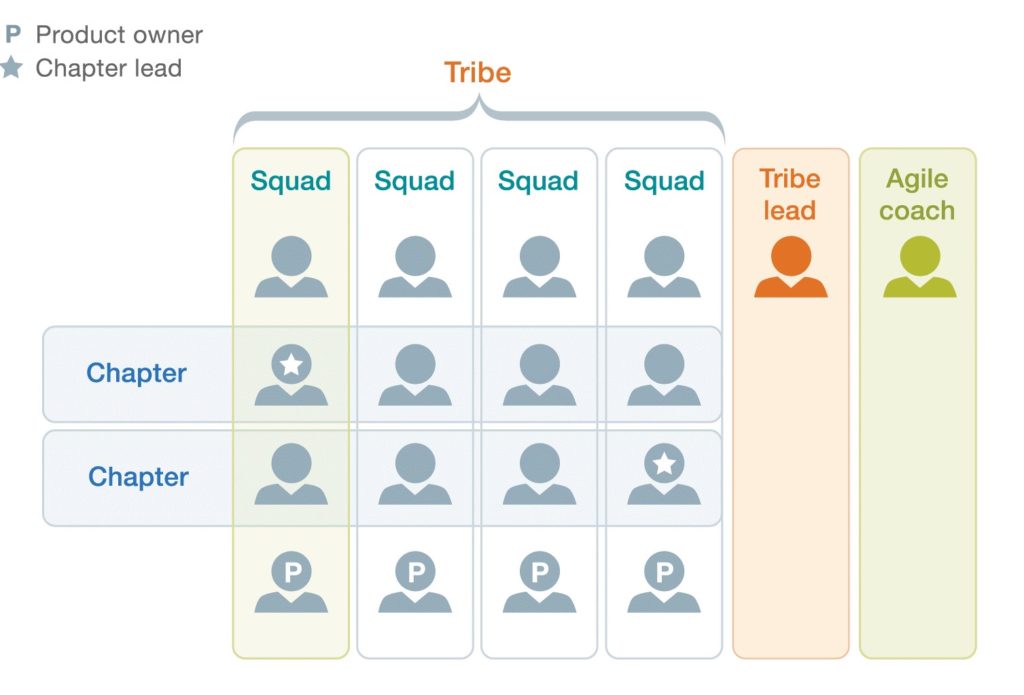

Those who remained were organized into squads, tribes, and chapters. Each squad was autonomous and was made up of nine people with different functions but working in the same space. Chapters ran across the squads, allowing knowledge to spread through the company. Tribes were collections of squads working on related missions and made up of around 150 people.

Squads were told to write down the goals of their projects. They agreed on ways to measure the impact their efforts have on clients and they decide for themselves how to manage their daily activities. Tribes organized scrums, took part in daily stand-ups, were responsible for “portfolio wall planning” and making sure that product owners were all working in the same direction. Tribes also took part in quarterly business reviews, an idea they borrowed from Google and Netflix. They listed their achievements and their biggest lessons and celebrated their successes and failures.

The company identified four elements that were essential in its transformation: an agile way of working that brought IT and commercial staff into the same buildings, working in squads, and testing offers without managers slowing collaboration; a horizontal organizational structure that reduced silos; an approach to devops that emphasized continuous delivery; and a “new people model” that focused on how people dealt with knowledge rather than assigning the highest status and salaries to the managers responsible for the biggest projects.

The goal of the transformation was to make ING bring products to market faster, “increase employee engagement, reduce impediments and handovers, and, most important, improve client experience.” The company said that it was “progressing well on each of these” and had increased software releases to every two or three weeks from five to six times a year. The bank asked INSEAD, a business school, to measure the metrics.

The impression that ING gives is that the bank’s transformation from a traditional financial firm to a technology business that delivers financial services with digital products was a success. Output has increased and customers may find that it’s now easier to take investment advice in person and implement that advice themselves.

But the transformation has come at a price. The company doesn’t say how many people it lost other than to say that it lost “a lot.” Nor do we see how production was affected during that fifteen-month transformation or whether there was a less disruptive route to the same outcome. Most importantly, we aren’t given an indication about whether a Spotify technology model is the most appropriate structure for a company that’s in the business of delivering financial services rather than streaming music or providing search results.

All the Agile Supply Chains of Benetton

ING saw itself as a bank that was transforming into a digital services company so adopting practices pioneered by technology firms might have looked like a natural step. Another industry that has taken up agile practices with enthusiasm, though, has nothing to do with technology—or software or even finance.

Over the last few years, the fashion industry has come to realize that the same principles that have improved the technology industry can also benefit them. They too used a traditional “waterfall” process: they would plan at least a year ahead the items that would be in fashion in the future. They would try to predict demand for those fashions, and they would load up on inventory in the hope that their predictions were right. They would then have to ship those items to stores around the country and around the world. If an area saw a surge in demand for colored socks, for example, they would have no way to respond before the season ended and tastes changed again.

But the fashion industry has changed. The same kind of just-in-time manufacturing processes that now characterize the automotive industry also make up much of the fashion world. Benetton, for example, uses external production, retail networks, indirect sales, and centralized management. But it also makes use of customer responses to stay flexible. Inventory is kept to a minimum while the clothes are produced in small cycles to ensure that stores are always full of the most popular items. According to one report, Benetton store managers must commit 80 percent of orders seven months in advance. The items are produced and delivered on a 20-day order cycle. A monthly stock rotation with daily order reports and feedback ensures that production can be adjusted immediately.

This isn’t a traditional agile transformation in the software industry. There’s no dependence on scrums and stand-ups, let alone Kanban boards and software updates. But what Benetton and other fashion firms have done fits exactly with the main principles of agile processes: it’s created a unique solution for a unique context that improves flow, improves communication between producer and customer, and gives the company responsiveness. The company depends on sophisticated IT systems to receive and organize customer responses, to distribute new orders, and to produce new designs inspired by customer feedback. For the fashion industry, agility takes place in the supply chain rather than in the manufacturing process or in the reshaping of organizational structure. Benetton’s workers have had it much easier than ING’s staff.

Not All That’s Agile Produces Agility

Those two examples of businesses outside the world of technology successfully adopting agile ways of working may be exceptional. A 1996 study has found that only 30 percent of all change programs succeed. The rest run into resistance, fail to be implemented, or don’t generate the results the change leader had predicted.

In early 2013, the UK’s Department for Work and Pensions stopped work on its plans to roll out Universal Credit, a new way of making welfare payments. According to the National Audit Office, more than 70 percent the £425 million spent by the department went on IT systems. It wrote off £34 million of that expenditure. The system was missing a number of important functions. There was no component to identify potentially fraudulent welfare claims, for example, so the Department needed to conduct multiple manual checks. That would have been impossible once the program had rolled out nationally.

The National Audit Office dismissed the notion that the cause of the failure was procurement or contractors. The problem, the Office said, was mainly a failure of Agile adoption. The work process had lacked transparency and performance reporting, exactly the sort of issues that agile workflows are meant to correct.

Nor was the British government the only one to get an agile implementation wrong. A similar problem struck the launch of Healthcare.gov, President Obama’s online health insurance marketplace. The site’s performance was so poor than only six of the four million people who accessed the marketplace on the day it was launched were able to purchase insurance.

The failure of Healthcare.gov had a number of causes. IT experts have criticized the project for lacking the right people and the right leadership. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) also found procurement mistakes with contracts awarded to businesses with no experience or expertise in these kinds of projects. The technology was also overly complex but the biggest flaw was the scope.

One principle of agile processes is that small is beautiful. Teams think big but start small and learn quickly. They start with Beta releases, test them, review the feedback then scale up. The developers of the Healthcare.gov website did none of that. Despite reports that the teams worked in sprints, covered the walls with story cards, and published code on Github, the creation of the marketplace had more in common with waterfall processes than with agile production.

It’s possible that the reason for that failure was the nature of the product itself. This was a government-led initiative that was also politically controversial. A Beta version of a minimum viable product of Healthcare.gov would have faced immediate attack by political opponents. The developers may have felt they needed to launch with a splash but the failure of agile reporting and review processes during development meant that by the time they realized the platform couldn’t cope with demand it was too late. Altogether the federal government spent around $840 million developing a site whose lack of agility meant that it didn’t work at all on launch.

Agile Works Anywhere… If It’s Implemented Carefully

Agile transformations and ways of working can work outside the technology industry. Some banks have managed to completely re-organize themselves, change entirely the way that they operate and the way that the company is structured to create more fluid workflows and greater collaboration. The fashion industry has reinvented supply chains to ensure rapid delivery and responsiveness to emerging tastes. Each of those are examples of agile at work.

But agile isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Each implementation has to be rolled out slowly, reviewed and adjusted. When those reviews don’t happen, the result is the same as old school waterfall production in which decisions are made early and left unchanged. Mistakes remain, compound and can cripple the product when it’s released.

The publication of the Agile Manifesto was a good start and its principles can work outside IT. But they’re only a framework—and they can fail inside IT too.

Recent Comments